Privacy as Infrastructure: What Brazil's Pix Teaches the World

Privacy was not a priority when developing the payment system Pix. What can we learn from this?

- Status update January 1st 2026: I am publishing the V1 version of this article. I plan to be doing some improvements in the next weeks, such as:

- Integration of images and illustrations

- Adding a quick overview with links to the corresponding sections

- Adding a Notebook LM audio overview

Summary

The provided text explores the security consequences of Brazil’s instant payment system, Pix, which prioritized speed and adoption over user privacy. While successful in achieving financial inclusion, the system’s design allows personal identifiers like phone numbers and tax IDs to serve as payment keys, leading to a systemic fraud epidemic.

The author argues that this lack of data compartmentalization creates national security vulnerabilities, especially as artificial intelligence enables scammers to weaponize leaked data at an automated scale. The source serves as a warning to policymakers worldwide that privacy must be treated as essential infrastructure rather than an optional feature.

Ultimately, the text advocates for privacy-by-design and data minimization to protect citizens and state institutions from evolving digital threats.

The Warning

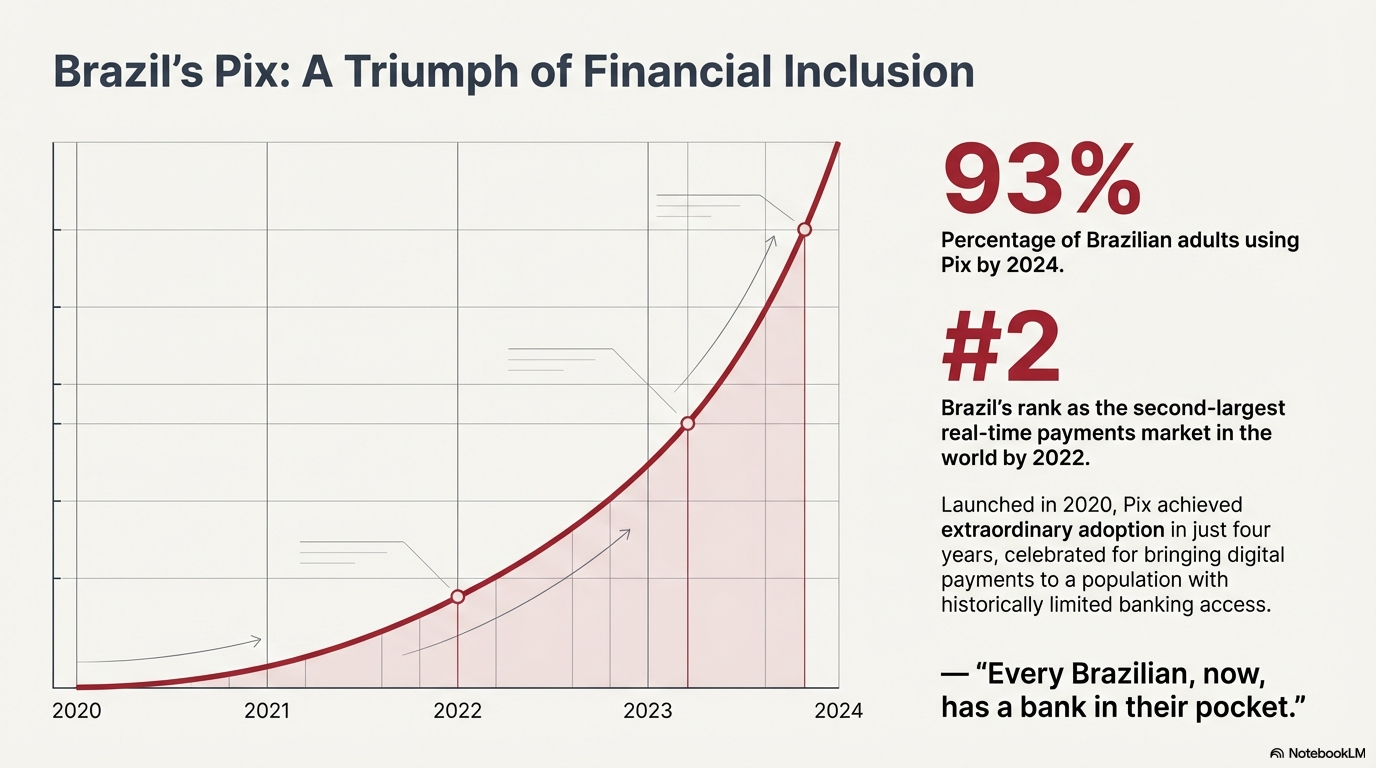

In November 2020, the Brazilian Central Bank launched Pix, an innovative instant payment system. Adoption was extraordinary. By 2024, 93% of Brazilian adults were using Pix, a feat for a system that was only four years old.

By 2022, Brazil had become the second-largest real-time payments market in the world, behind only India. Pix was celebrated as a triumph of financial inclusion, bringing digital payments to a population with historically limited banking access. As one cybersecurity expert puts it, "every Brazilian, now, has a bank in their pocket."

But something else was built alongside the payment rails. It was quieter, less visible, and harder to explain in a press release.

Brazil was constructing critical infrastructure with a weakness baked into the foundation: inadequate privacy protections.

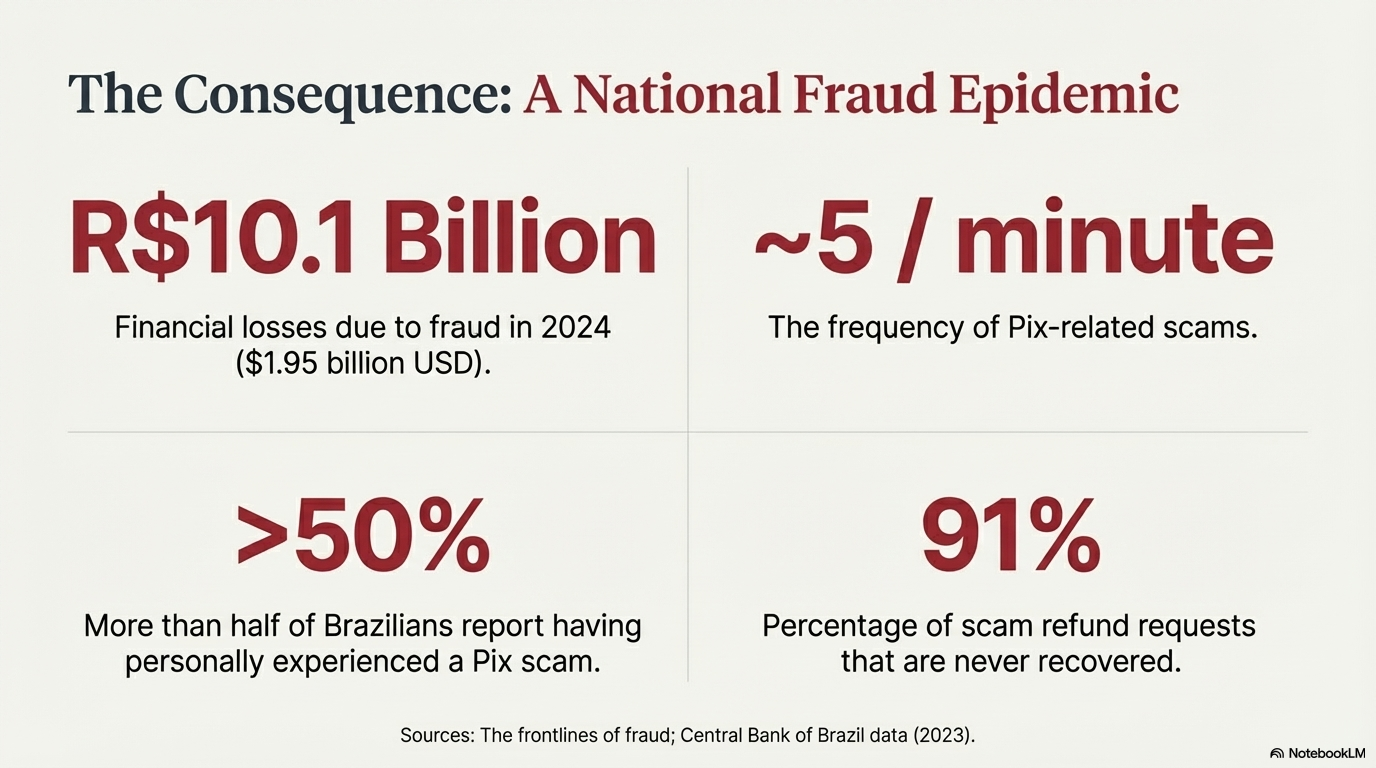

The downstream effects are not subtle. Pix-related scams have become incredibly common in Brazil. Almost five scams happen every minute. More than half of Brazilians say they've personally experienced one.

These are not edge cases. This is a systemic crisis affecting tens of millions of people.

This is also not a story that stays in Brazil. It is a warning to every country building instant payment infrastructure. It also matters to open-source and Bitcoin developers for a more specific reason. Since the cypherpunks, privacy has been treated as a core value, not an added luxury. Pix reinforces this argument by providing a real-world example of what happens when privacy is not taken seriously.

When payment infrastructure is designed without privacy as a foundational requirement, the consequences extend far beyond "some users got scammed." Vulnerabilities spill across boundaries. Criminals exploit them. Corporations absorb damage. Foreign actors use them against the state itself.

Brazil made a choice, whether consciously or not, to deprioritize privacy in the design of Pix. The failure of compartmentalization, discussed below, is the clearest evidence of that choice.

And it seems like this is about to get worse. What used to require patient criminals and careful social engineering is moving toward repeatable, automated workflows.

Everyone involved in building payment infrastructure should ask the same question, whether writing code, advising on policy, or making political decisions about implementation:

Are we making the same mistake?

The Design Choice

Pix was designed for speed, convenience, and mass adoption. On these metrics, it succeeded spectacularly. The system processes transactions in seconds, operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and achieved penetration rates that most central banks can only dream of.

However, speed and convenience should not have been the only guiding values in its development. Privacy should have been a foundational requirement.

It was not. This was not malicious. No one can know for sure, but it appears to have stemmed from incorrect assumptions about the threat environment and a fundamental misunderstanding of what instant payments would enable.

What Compartmentalization Means

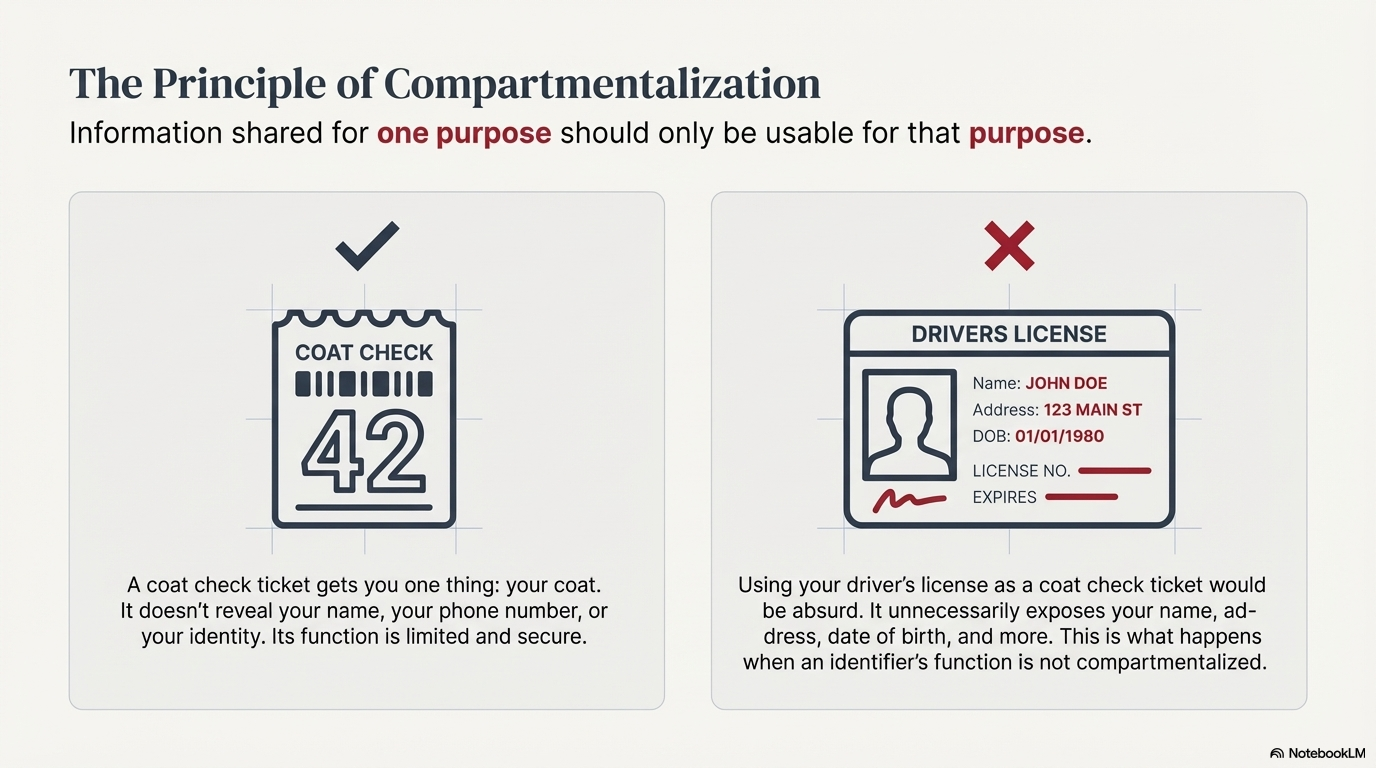

Compartmentalization is a core principle of information security. In plain terms: information shared for one purpose should only be usable for that purpose.

Consider a coat check at a theater. A person hands over a coat and gets a numbered ticket. That ticket does one job. It gets the coat back.

The number doesn't reveal identity. It can't be used to claim another coat. It can't be turned into cash. It can't be used to learn a name, a seat assignment, or whether the person has attended before. The ticket is functionally limited. It enables one action and nothing else.

A payment system designed with compartmentalization would work similarly. If I share a payment identifier with you so that you can send me money, that identifier should enable exactly one thing: the transfer of funds. It should not reveal my phone number, my government ID, my full legal name, or any other information that could be used for purposes beyond the transaction.

A privacy-prioritizing design would enforce that separation automatically. Users would not need to be experts. They would not need to "choose" privacy. The system would keep payment information in its lane.

How Pix Violated This Principle

Pix allows users to register four types of payment identifiers, called "Pix keys":

- CPF (the Brazilian individual taxpayer identification number, equivalent to a Social Security Number)

- Email address

- Mobile phone number

- Random alphanumeric identifier

Only the fourth option, the random identifier, respects compartmentalization. The other three take personal information that exists for entirely different purposes and repurpose it as a payment address.

This sounds harmless until it touches real life.

Imagine a routine exchange: a small job, a quick payment. Someone hires a person to mow a lawn. The work is done. The customer asks for a Pix key. The worker shares a phone number.

That exchange now gives the customer more than the ability to pay. It also gives the ability to call, text, and message on WhatsApp. In other words, the payment identifier isn't confined to payments. It leaks into everything else a phone number unlocks.

Why This Happened

Two explanations emerge for this design choice.

The first is usability optimization. Requiring people to remember a new piece of information, a random alphanumeric string, was perceived as an obstacle to adoption. Allowing people to use information already memorized (such as phone number, email, CPF) removed friction. It favored convenience over privacy, apparently without full consideration of the consequences.

The second explanation is legacy thinking. Brazil's previous money transfer methods (TED, DOC) required disclosure of substantial personal information, but those systems were typically used between parties who already had some level of trust: banks, businesses, known individuals. Sharing personal information in those contexts was less dangerous because the relationships were usually pre-established.

The Central Bank openly stated that Pix key data (name, CPF, phone, bank info) were not "sensitive" since such details already appear on checks or wire transfers. This reflects a legacy system mindset: in older payment systems, exchanging personal info was normal. But those systems operated at a far smaller scale and in a different threat environment.

Pix changed the landscape. It enabled instant payments between strangers in contexts analogous to cash transactions. The street vendor does not know their customers. The person selling goods on social media does not know their buyers.

Cash-like transactions require cash-like privacy. Pix introduced systemic risk by not providing the privacy levels required.

The Tell

Here is the fundamental point: a system that treats privacy as foundational would not make personal identifiers double as payment identifiers without warning users what that exposes. It would default to a privacy-preserving alternative and present phone numbers, emails, and CPF as exceptions with clear, explicit privacy trade-offs.

The compartmentalization failure is the symptom. The remaining problems described below trace back to this original design mistake: fraud at scale, cascade effects with data breaches, and exposure to foreign intelligence operations.

The Consequences

What happens when a nation builds payment infrastructure without prioritizing privacy? Brazil provides the answer.

The Fraud Epidemic

In 2024, Brazil's financial sector reported R$10.1 billion in losses ($1.95 billion USD) related to fraud. More than half of Brazilians say they've personally experienced it.

For every Real stolen, banks spend up to R$4.49 in response and recovery. This is not just costly, it's systemic.

Fraud is now estimated to cost the country between 0.35 percent and 0.4 percent of GDP, a figure that likely understates the true impact.

Source: The frontlines of fraud: How Brazil is becoming a global testbed for financial crime prevention

The scams follow predictable patterns. They lean on the personal details Pix exposes: names, banks, and contact information. Those details turn ordinary users into easy targets for social engineering.

Common scam patterns

The fake bank employee scam exploits the information criminals gather from Pix transactions and data breaches. As digital forensics expert Wanderson Castilho explained, having a victim's basic Pix info (full name, CPF, etc.) lets the scammer pose as a bank agent and extract even more sensitive data like passwords or OTP codes, because the victim is tricked into thinking only their real bank would know those details. A little accuracy buys a lot of access.

The WhatsApp family emergency scam involves criminals compromising or simulating a victim's family member's WhatsApp account, then contacting the victim claiming to be a relative in urgent need of money. The criminals already know the family relationships from breached data, which gives the message weight.

The fake auction scam sees criminals take over social media accounts and use them to sell goods at attractive prices. Victims pay via Pix. The goods never arrive. The criminals disappear with funds that were transferred instantly and irreversibly.

The Cascade Effect

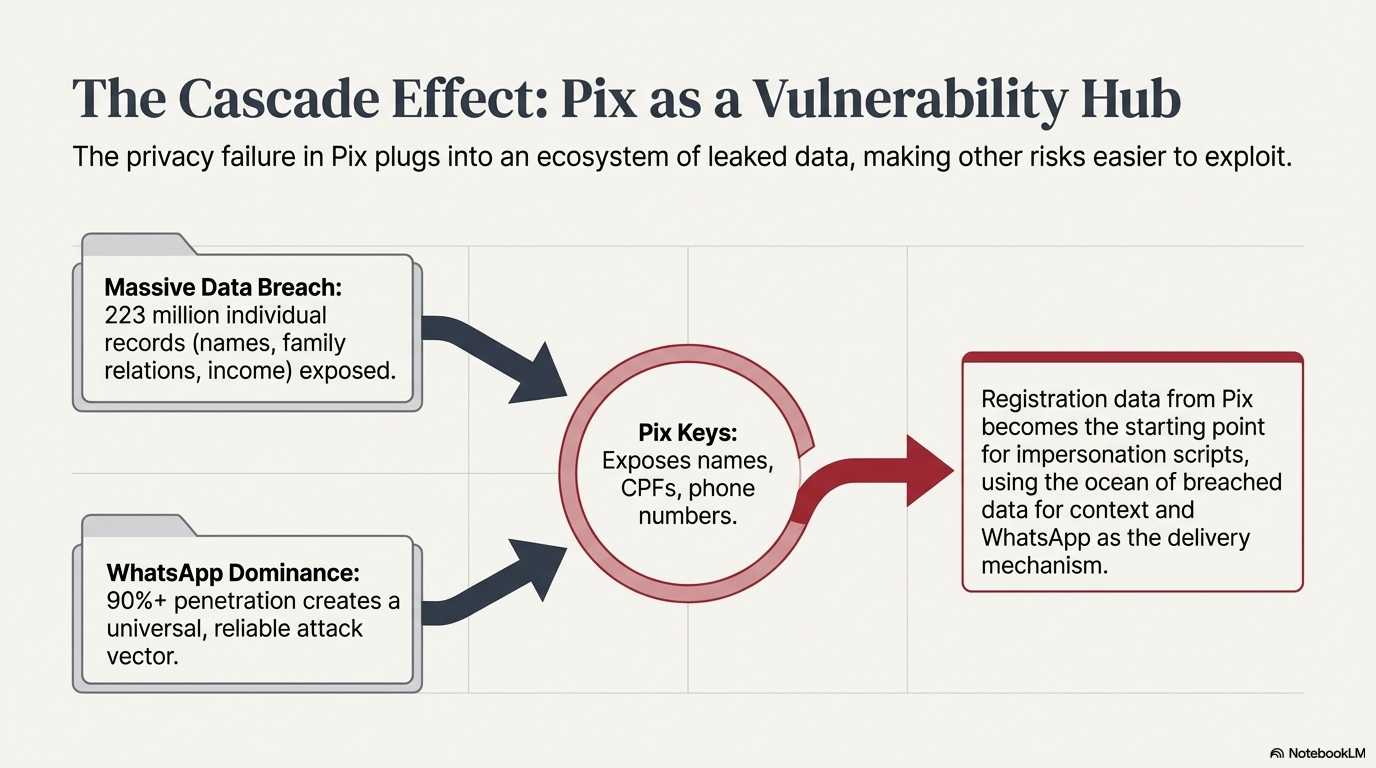

Pix does not exist in isolation. It sits inside an ecosystem of leaked data, social media oversharing, and ubiquitous messaging apps. The privacy failure in Pix doesn't replace these risks. It plugs into them and makes them easier to use.

The data breach landscape

Brazil experienced its largest-ever data breach in January 2021, exposing detailed personal information on 223 million individuals, more than the country's living population (213 million in 2021) because deceased individuals were included. Google Search even indexed it at one point.

The breached data encompassed names, CPF numbers, birth dates, addresses, income levels, and family relationships. This information is available for purchase on dark web forums for fractions of a dollar per person.

Separately, Pix keys themselves have been leaked. In late 2021 and early 2022, about 576,000 Pix keys (with associated names, CPFs, phone numbers, etc.) were unintentionally exposed through bank APIs. The authorities insisted that since no passwords or financial balances were leaked, only "registration data," the incident posed minimal risk.

"Registration data" sounds minor until it becomes the starting point for an impersonation script.

The WhatsApp factor

Brazil has one of the highest WhatsApp penetration rates in the world. More than 90% of smartphone owners use the app. The expression "to send a 'zap' (diminutive form of WhatsApp)" has become a colloquial verb meaning to message someone.

This homogeneity creates a reliable attack vector. If a criminal knows a Brazilian's mobile phone number, they can almost certainly reach them via WhatsApp. And since phone numbers can be used as valid Pix keys, the payment system creates a direct pipeline to the messaging platform where fraud is executed.

Social media and express kidnapping

According to the study published on Statista, Brazil ranks first globally with an average daily social media usage of 3 hours and 49 minutes, more than any other population in the world.

Like people elsewhere, Brazilians have embraced social media as a platform for self-expression and social connectivity. However, sharing personal information publicly without considering the consequences creates opportunities for criminals to exploit.

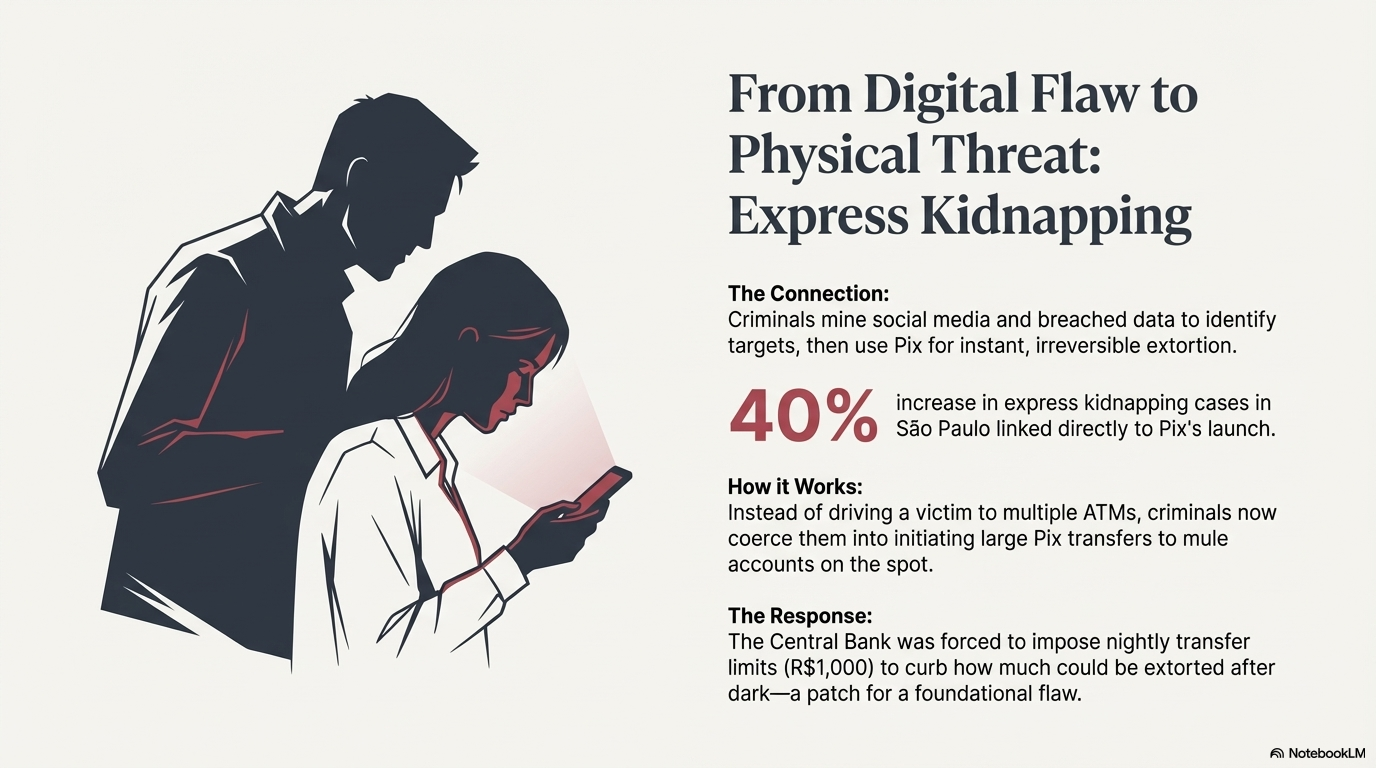

This sharing takes on a different character when combined with Pix. Criminals mine social media for targets, gathering details about routines, locations, and financial status. They use this intelligence to select victims for express kidnapping, aiming for people who can be forced into substantial Pix transfers.

Traditional express kidnappers in Brazil, who abduct victims off the street to force quick ransom payments, quickly learned that Pix is the perfect extortion tool. Rather than drive someone to ATMs, criminals now coerce the victim into initiating Pix transfers to mule accounts on the spot.

In São Paulo, police linked a spike in express kidnapping cases, a 40% increase at one point, directly to Pix's launch, as criminals exploited its speed. The problem grew so severe that the Central Bank imposed nightly limits (around R$1,000) on Pix transfers by default to curb how much could be extorted after dark.

The State Actor Factor

The vulnerability Pix creates extends beyond criminal fraud. It represents a national security exposure, and foreign hacker groups are already exploiting Brazil's digital infrastructure.

According to Google's Threat Analysis Group and Mandiant, more than 85% of government-backed phishing activity targeting Brazil originates from three countries: the People's Republic of China, North Korea, and Russia. Since 2020, at least 15 PRC cyber espionage groups have targeted Brazilian users, accounting for over 40% of state-sponsored phishing campaigns against the country. These are documented, ongoing operations.

The targeting is systematic and strategic. In August 2023, a PRC campaign targeted nearly 200 users within a Brazilian executive branch organization. In late 2022, Chinese actors used anonymizing relay networks to launch phishing campaigns against nearly 2,000 email addresses, including 70 belonging to Brazilian state government organizations. Brazil's military, national government, diplomatic institutions, and provincial governments have all been targets.

North Korean government-backed groups have focused on Brazil's aerospace, defense, technology, and financial services sectors. At least three North Korean groups have specifically targeted Brazilian cryptocurrency and fintech companies. Russian groups, particularly APT28, targeted over 200 Brazil-based users in large-scale phishing campaigns as recently as late 2021.

Brazil's Pix system, combined with the massive data breaches affecting 223 million records, creates a target-rich environment these actors can exploit. Leaked data reveal patterns of relationships, habits, locations, and vulnerabilities. A foreign intelligence service seeking to identify, profile, and potentially compromise Brazilian citizens has extraordinary resources at its disposal.

Google's researchers note that Brazil's "rise of the Global South" status makes it an increasingly attractive target:

As Brazil's influence grows, so does its digital footprint, making it an increasingly attractive target for cyber threats originating from both global and domestic actors.

The threat extends directly to financial infrastructure. Google documented malware specifically designed to target Pix, including "GoPix," which hijacks clipboard functionality during Pix transactions to redirect payments to attacker-controlled accounts.

Based on ransomware data leak sites, Brazil is now the second most targeted country in the world for multifaceted extortion, behind only the United States.

These are not Pix design flaws, it's a national security problem.Bruno Diniz, 'Pix Gangs' cash in on Brazil's mobile payments boom, Reuters

Brazil did not just create a fraud problem. It created a national security vulnerability that state actors are actively exploiting.

Regulatory Failure

The Central Bank has scrambled to patch holes. It introduced a special refund mechanism for scam victims called "MED" to allow fraud victims to claim money back. Yet even those measures have struggled.

In 2023, of 2.5 million Pix scam refund requests, 91% of them were never recovered. Scammers had already emptied the destination accounts.

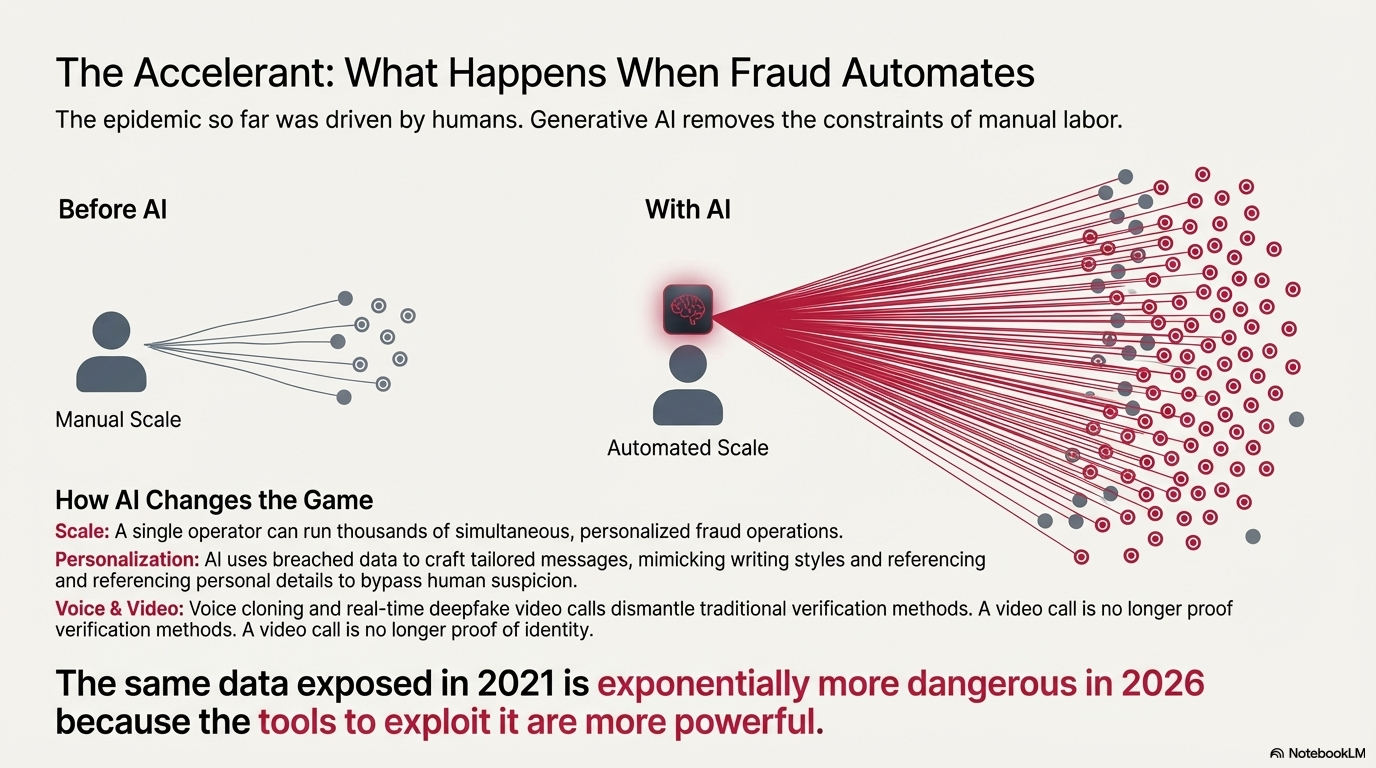

Most of this damage was done by humans working at human speed. People researching targets. People crafting messages. People pushing victims through a script, one conversation at a time.

That is the baseline. The floor.

What comes next is worse.

The Outlook

Scammers are leveraging advanced technology to launch more sophisticated attacks at scale. They are using AI to boost inherited trust to unprecedented levels—automating hits; improving scam content, scope, and reach; and driving more effective social engineering techniques. And they are also reaping the rewards more easily, using synthetic identities to set up receiving accounts that bypass traditional controls.

Added to this is the rise of real-time payments, which has reduced the window of opportunity to spot and stop scams. Our data reveals that APP fraud through real-time payments is predicted to increase from 63% of all APP fraud losses in 2023-2024 to 80% by 2028.

2024 Scamscope by ACI Worldwide: APP scam trends in the U.S., the U.K., Australia, India, Brazil, and the UAE

So far, the story has involved humans doing human things: research, persuasion, repetition. That built an epidemic already.

Generative AI removes the staffing constraint. It doesn't need rest. It doesn't get bored. It doesn't forget details.

The same exposed identifiers and leaked data breach are becoming the raw material for the automation of scams, which are becoming increasingly sophisticated.

What AI Changes

Scale

Before generative AI, a skilled scammer might target dozens or hundreds of victims personally. Research took time. Conversation took time. Managing a handful of parallel chats was work.

With AI, that ceiling collapses. A single operator can run thousands of simultaneous personalized fraud operations. The marginal cost of adding another victim becomes negligible relative to the scale of the campaign.

Personalization

Older phishing attempts were often obvious. Generic greetings and awkward phrasing were tells. Many people learned to filter them out.

AI removes that clumsiness. Using oceans of breached data, an AI system can craft tailored messages. It can reference personal details, mimic writing style, and avoid common red flags. Security firms report early instances of AI-authored scam emails so realistic that even trained professionals have trouble distinguishing them.

Voice and video

The WhatsApp family emergency scam has historically relied on text. Many people learned a simple rule: call back on a known number before sending money.

Voice cloning technology now requires only seconds of sample audio to generate convincing synthetic speech. A voice message scraped from Instagram, a video posted to TikTok, a clip from a family WhatsApp group can provide enough raw material. McAfee researchers showed how easy-to-use AI voice generators enabled a wave of new phone scams, with criminals using synthesized voices of victims' loved ones to demand money.

In Brazil, police recently busted a group that used AI-generated videos of a famous model to promote a fake investment, stealing millions of dollars before the deepfake was discovered.

The familiar verification mechanism, "I know what my son sounds like," is losing its force.

The threat goes beyond voice cloning. Tools like Deep-Live-Cam, which went viral on GitHub in mid-2024, enable real-time face-swapping during live video calls using just a single reference photo. Similar applications now offer simultaneous voice conversion, allowing a scammer to appear and sound like someone else during an actual conversation.

These tools run on consumer hardware and require technical skill. But the implication is direct. A video call is no longer proof of identity.

Hong Kong police reported a case where finance worker transferred $25 million after a video call with what appeared to be the company's CFO. Every participant in the video call, except the victim, was an AI-generated deepfake.

The Time-Bomb Nature of Exposed Data

A common assumption is that leaked data becomes less dangerous over time. People move. Addresses change. Phone numbers change. Old email accounts are abandoned.

That assumption is dangerously wrong.

Some data decays. But the most sensitive identifiers do not. Social Security Numbers are permanent. Full legal names rarely change. Family relationships persist across decades.

CPFs (Brazilian Social Security Numbers), included in Brazil's 223 million record breach, remain connected to specific individuals for a lifetime. This connection cannot be severed. These are anchors that allow attackers to re-correlate and refresh the decaying elements. Your phone number changed? Your CPF did not, and it can be used to find your new one.

More fundamentally, exposed data becomes more dangerous because attack capabilities advance faster than data decays.

The massive Brazilian data breach in 2021 exposed 223 million records. At the time, exploiting that data required human effort. The data was dangerous, but exploitation was limited by human capacity.

That same data in 2026 is far more dangerous. AI can process, correlate, and weaponize it at scale. Capabilities that did not exist for "regular individuals" when the data was leaked now do.

Consider what AI can already do with a simple photograph. Systems can now identify the precise location where a photo was taken without any metadata whatsoever. By analyzing visual elements like architectural styles, vegetation patterns, street signs, topography, and even the angle of shadows, AI models can pinpoint locations with startling accuracy. A photo you took in 2021, stripped of all metadata, can be geolocated in 2026 purely through visual analysis. The image itself has not changed, but the capability to extract information from it has advanced dramatically. The same dynamic applies to exposed data. The information remains static while the tools to exploit it become more powerful.

The same data in 2028 or 2030 will be more dangerous still. Exact attack technologies are hard to predict. The direction is easier to predict: more capable, more scalable, more convincing.

That is why privacy must be a design priority, not an afterthought. The safest assumption is that whatever is exposed will eventually be used.

Brazil has no such protection. The 223 million breached records exist. The permanent identifiers remain valid. The attack surface grows daily. The tools available to exploit it advance continuously.

Yet, while Brazil suffers the consequences of collecting and centralizing what should never have been gathered, some governments continue to view privacy-preserving infrastructure as a threat rather than a safeguard.

A Possible Shift in Government Thinking

The persecution of privacy tool developers is not new. In the 1990s, Phil Zimmermann faced a three-year criminal investigation for creating PGP email encryption software. The government treated encryption as a weapon and threatened him with five years in prison simply for publishing privacy-protecting code. The investigation was eventually dropped, courts ruled that code is speech, and export restrictions on encryption collapsed entirely by the 2000s.

Today's prosecutions of cryptocurrency privacy tool developers echo this history, though with added complexity. Whether current cases represent similar government overreach or legitimate enforcement against deliberate criminal facilitation remains contested.

What is not contested is Brazil's experience: privacy-neglecting infrastructure creates catastrophic vulnerabilities when breached, while privacy-by-design prevents the failure mode entirely. The question governments must answer is whether privacy infrastructure serves law enforcement goals or undermines them. Brazil's crisis suggests the former.

Why This Changes the Urgency

Countries designing payment systems in 2020 could perhaps be forgiven for not fully anticipating AI-enabled threats. The technology was less mature. The implications were less obvious.

That context has changed. Any country building instant payment infrastructure in 2026 must account for the AI threat environment. Privacy deprioritization was an oversight in 2020. In 2026, with the threat landscape clearly documented, it represents a more deliberate choice, with known consequences. Threat models have changed. System requirements must change accordingly.

Brazil cannot easily undo its choices. The system is built. The patterns are established. Retrofitting privacy into an architecture designed without it is expensive, disruptive, and often incomplete.

Other countries still have a choice. They can learn from Brazil's experience before they repeat it. The question is whether they will.

The Stakes

Why does this matter beyond Brazil?

Because payment systems function like other infrastructure: they’re shared rails everyone depends on. When those rails fail or get exploited, the damage doesn’t stay with the unlucky user. It spreads, the way a power outage or a contaminated water line quickly becomes everyone’s problem.

The Infrastructure Argument

Payment systems share three characteristics that make privacy design an infrastructure issue.

Essentiality

Modern life is impossible without access to payments. Rent, groceries, wages, and basic commerce depend on these systems.

Universality

Payment systems must serve everyone. The wealthy and the poor. The technically sophisticated and the digitally naive. Urban professionals and rural farmers. Failure does not stay contained.

Systemic risk

Infrastructure failures cascade. A compromised power grid affects hospitals, water treatment, and communication networks. A compromised payment system creates cascading risks across the economy and institutions.

Design choices in payment systems are not ordinary product decisions. They are infrastructure decisions with long-lasting consequences for entire populations.

Who Is Harmed

When privacy is not prioritized in payment infrastructure, harm spreads across citizens, corporations, and the state itself.

Citizens bear the most direct harm. They are targeted for fraud. They lose money to scams. They can face physical danger when criminals use payment data to identify lucrative robbery targets.

The most vulnerable suffer most: the elderly, the poor, and the less educated. The burden falls on those least equipped to carry it.

Corporations face their own harms. Employees become targets for social engineering. Criminals use payment data to map relationships and craft convincing attacks. The recent fraud schemes targeting companies with fake supplier invoices via Pix are a good example. Reputational damage follows when customers are harmed through the payment systems companies use.

The state itself is harmed by privacy-deprioritizing infrastructure. Government employees become targets for foreign intelligence and hacker operations. Economic stability suffers when widespread fraud undermines trust in financial systems. Institutional credibility erodes when the government is seen as having helped create the conditions for large-scale fraud.

This shifts the political calculus. Privacy protection is not opposed to state interests. It is a state interest.

The Asymmetry

The current situation benefits attackers and burdens defenders.

Attackers benefit from exposed data. Every detail provides leverage. Every connection enables targeting. Every pattern reveals vulnerability.

Defenders must protect everything. Attackers need one opening. That asymmetry grows as attack capabilities improve. AI amplifies the advantage of those exploiting exposed data while providing less protection to those being targeted.

Europe's GDPR enshrines data minimization as a legal requirement precisely because regulators recognized what Brazil is now learning: you cannot secure what you should not have collected.

Privacy-by-design is the only defense that scales. It reduces what attackers can access and lightens the defensive burden. Brazil chose the opposite approach. The costs are already visible.

The Principle

What would it mean to prioritize privacy in payment infrastructure, not as an add-on, but as a foundational system design requirement?

Privacy as System Design Requirement

Prioritizing privacy means treating it as a constraint that shapes architecture from the beginning, even when that feels inconvenient.

Before defining data structures: What is the minimum information necessary for this transaction to occur?

Before designing user interfaces: What information will be displayed, and to whom, under what circumstances?

Before establishing identifier systems: How do we enable payments without exposing identity?

Before integrating with other systems: What data will flow across boundaries, and how do we contain it?

These questions matter most at the beginning, when choices are still open. Once architecture is set, retrofitting privacy is expensive and incomplete.

Compartmentalization as Essential Expression

If privacy is the commitment, compartmentalization is one essential way that commitment manifests in system design. A properly compartmentalized payment system would have specific characteristics.

By default, payment identifiers reveal nothing about identity

It’s fine if a user chooses to customize a payment identifier to make it easier to remember. But the default should be a privacy-preserving identifier with no link to the person’s real-world identity. The information shared to receive a payment should not be tied to a name, phone number, government ID, or other personal details. Ideally, it works for payments and nothing else.

Transaction confirmations show minimum necessary information

Confirmation should be just enough to prevent misdirected payments, but minimal enough that it doesn’t become useful fuel for scrapers trying to harvest data.

The system enforces these boundaries automatically

Users should not need to "choose privacy." The system should protect them by default because it was designed to do so.

A privacy-prioritizing design would make safe identifiers the default, not an option buried in settings that most users never explore.

The Sanitation Analogy

Water safety is not delegated to each household. Infrastructure delivers safe water by default through treatment, distribution, and controls.

Privacy in payment systems follows the same logic.

It is unrealistic to expect every person to understand identifier types, configure settings correctly, detect sophisticated scams, and remain vigilant indefinitely. Some will succeed. Many will fail. The vulnerable will pay the highest price.

The alternative is infrastructure that protects everyone by default. Payment rails that do not expose users to exploitation simply by participating.

The Test

Every payment system design team should be required to answer this question:

If this data leaks, and it will, what can attackers do with it?

Breaches are not hypothetical. The question is what happens when the data is compromised.

Now add the AI dimension:

What can attackers do with this data and AI assistance?

This raises the bar. Data that might be marginally exploitable by humans becomes devastatingly exploitable at AI-enabled scale. The acceptable level of exposure drops.

Brazil's Pix would fail both tests. The data that leaks enables targeting. With AI assistance, it enables targeting at scale.

Future-Proofing

Attack technologies will evolve. Exact forms are hard to predict. Growth in capability is not.

Uncertainty itself argues for privacy prioritization. Data that is never exposed cannot be exploited by technologies that do not yet exist. Compartmentalization that is rigorous today remains protective against future attacks.

Brazil has no such insurance. The data is exposed. The architecture is set. Whatever attack technologies emerge will find million profiles waiting to be exploited.

Other countries can make a different choice, but only if privacy is prioritized now, before systems are built and data is exposed.

The Call

A paradox sits at the center of modern data protection. Governments often mandate extensive data collection to combat crime. When breaches occur, they respond by expanding surveillance systems to monitor and correlate even more data.

This approach treats privacy-preserving businesses as suspicious anomalies. It assumes transparency to authorities equals safety, while privacy equals potential criminality.

Brazil's Pix system points to a more basic problem: the mandatory collection and exposure of personal information. If the data were not collected and repurposed in the first place, it could not be breached, leaked, or weaponized.

Instead of accepting a cycle of "collect everything, then surveil everything," the foundation deserves scrutiny: Do systems actually need this data to function? The technology for maintaining privacy exists. Data minimization attacks the problem at its root.

The lessons of Brazil's experience with Pix are available to anyone willing to learn them. The open question is whether policymakers, designers, and citizens will act on those lessons before it is too late.

For Policymakers and Stakeholders

Mandate privacy as an explicit design requirement

Do not leave it to the discretion of technical teams or the vagaries of product development. Make privacy a stated requirement with the same standing as security, scalability, and reliability. Require documentation of how privacy will be protected. Create accountability for privacy failures.

Require privacy impact assessments before deployment

Before any national payment infrastructure goes live, demand a rigorous assessment of what data will be exposed, to whom, under what circumstances, and with what consequences. Include adversarial analysis. How could criminals exploit this system? How could foreign actors use it for intelligence gathering? What happens when the data leaks?

Factor AI-enabled threats into threat models

The threat environment of 2026 is not the threat environment of 2020. Any system designed today will operate in an environment of AI-powered attacks. Design requirements must account for this. If threat models do not include AI-enabled fraud at scale, those models are incomplete.

Understand that privacy protects the state too

The state is not separate from the population. Government employees also use payment systems. Privacy deprioritization exposes the state along with citizens. Protecting privacy supports stability of state functions.

Support open source development, don't criminalize it

Governments have a lot to learn from Bitcoin and open-source payment development. Not every approach should be copied, but the process matters: trade-offs are debated in public, assumptions get challenged early, and security and privacy weaknesses get stress-tested by people motivated to find them.

That kind of scrutiny is a feature for critical infrastructure. It helps surface failure modes before they harden into national systems that citizens, companies, and institutions can’t easily escape.

Instead of treating privacy tool developers as suspicious by default, governments should study what works, how it works, and why. Then translate those lessons into public payment infrastructure, in ways that reduce exposure for individuals, limit fraud and operational risk for companies, and improve resilience for state institutions.

For Payment System Builders

Treat privacy as foundational, not optional

Build privacy into architecture from the beginning. Treat it as a constraint that shapes every decision rather than a feature to add later.

Apply compartmentalization rigorously

Ask of every data element:

- Does this need to exist?

- Does it need to be displayed?

- Does it need to be shared?

- Could it be separated from other data elements?

Default to separation and minimization.

Assume breach

Design for the scenario where data is compromised, because eventually it will be. The key question is what the breach enables. Minimize those consequences.

Design for 2030, not 2026

Threat environments evolve rapidly. Systems built today may operate for decades. Design for the future, not the past.

Make safe choices the default

If a privacy-protecting option exists, make it the default. Do not bury it. Do not require users to understand risks and opt in.

Study existing privacy-preserving payment implementations

The technical foundations for privacy-respecting instant payments already exist. Bitcoin's Lightning Network, for instance, demonstrates how payment routing can occur without exposing sender and receiver identities to the broader network.

While Lightning adoption remains modest compared to centralized systems, its architecture (especially the BOLT12 spec) embodies compartmentalization principles: payment channels reveal information only to direct counterparties, invoices can be generated without disclosing personal data, and the protocol separates identity from payment routing by design.

These are not theoretical constructs. They are deployed systems processing real transactions across dozens of countries. Builders of national payment infrastructure can examine what these implementations got right technically, even if the specific technology or adoption model differs from their context.

For Citizens

Demand to know whether privacy was prioritized

Citizens can ask representatives and regulators: was privacy a design requirement for payment infrastructure? What information is exposed in a transaction? What happens to that information?

Ask the basic question

Why does this system need my personal data to function?

If the answer is unclear, or if the answer is convenience rather than necessity, that is a warning sign.

Understand the limits of personal vigilance

Individual caution helps, but it cannot compensate for systemic exposure. When infrastructure makes people targets by design, safety becomes political. It depends on decisions already made.

Advocate for privacy as infrastructure

Privacy can be treated as a public good. It can be built into systems as a default condition, not a personal preference.

The Window

Many countries are building instant payment infrastructure right now. Central banks around the world are developing CBDC systems. Fintech companies are deploying new payment rails. The decisions being made today will shape financial lives for decades.

The time to prioritize privacy is before deployment. Once systems go live, data flows, and dependency sets in, course correction becomes difficult.

Brazil cannot easily undo its choices. The 170 million Pix users, the exposed data, and the architectural decisions that baked in privacy deprioritization are now the reality.

Other countries still have choices. But the window is open now, and it will close with each system that goes live without privacy as a foundational requirement.

A Note of Possibility

There is a chance that the very threats documented in this study may force a reconsideration by governments. As AI-enabled fraud scales and costs become undeniable, governments may come to see privacy-preserving payment solutions as protections rather than threats.

Technology for privacy-preserving payments already exists. Cryptographic techniques such as Chaumian ecash, zero-knowledge proofs, and layer-two solutions are not theoretical. They are reaching maturity to be deployed today.

If Brazil's crisis, amplified by AI, demonstrates clearly enough that privacy deprioritization is a national security threat, that political calculus may shift. Countries watching Brazil may conclude that the short-term convenience of surveillance-compatible design is not worth the long-term cost in fraud, instability, and foreign exploitation.

Conclusion

Pix showed what’s possible when a central bank pushes instant payments to mass adoption. It also showed what happens when privacy lags behind: the system becomes easier to exploit.

Brazil's experience is not a local curiosity. It is an early version of a problem other countries will face as real-time payments expand and as AI turns leaked, mundane identifiers into precision tools for coercion, impersonation, and mass targeting. In that environment, "be careful" is not a safety strategy. It offloads infrastructure failure onto the public.

The lesson is simple and hard. Privacy cannot be bolted onto critical infrastructure after adoption. Once millions depend on the rails, every fix becomes expensive and partial. The only moment where privacy is cheap is before deployment, when the system architects can still decide what the system reveals by default.

Privacy can be treated the way sanitation is treated. Build it into the pipes. Enforce compartmentalization. Minimize data collection because breaches are not a possibility, they are a timeline. Prepare for 2030 because attackers already are.

Brazil does not get to rewind. Other countries still can. The choice is not between privacy and safety. Brazil shows the opposite. Privacy is what makes safety possible at scale.